Hyperloop technology promises to zip passengers from Pittsburgh to Chicago in less than an hour, but Western Pennsylvania’s mountains, valleys and rivers could slow it down.

Two potential hyperloop proposals plan to connect Pittsburgh to Chicago via cities in Ohio in the coming decades but both recognize that tunnels and bridges might slow down the projects and increase the costs.

“Definitely on our study map we recognize that a majority of the corridor — when it comes to hyperloop from Newark, Ohio, all the way over to Pittsburgh — is going to have to be bridged or tunneled, depending on what it is,” said Thea Walsh, director of transportation and infrastructure at the Mid-Ohio Regional Planning Commission, one of the groups proposing a hyperloop project that would include Pittsburgh.

The Mid-Ohio Regional Planning Commission has proposed the Midwest Connect Hyperloop with Virgin Hyperloop One. This plan would connect Pittsburgh to Columbus to Chicago, with some stops in smaller cities in Ohio and Indiana along the way.

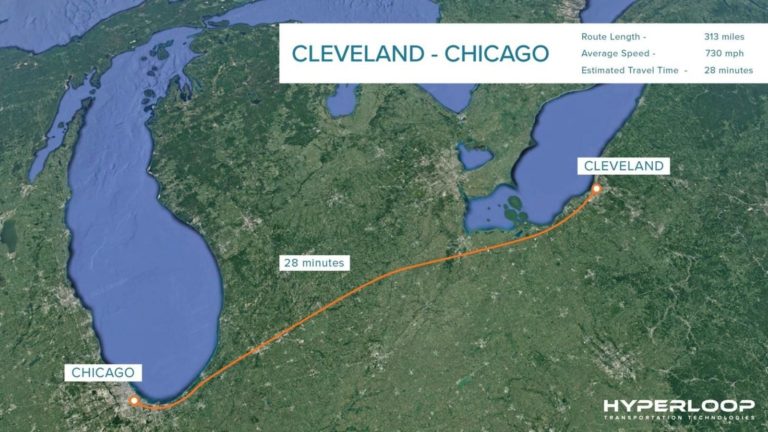

The Great Lakes Megaregion Hyperloop is outlined by the Northeast Ohio Areawide Coordinating Agency. The agency is working with Southwestern Pennsylvania Commission on the Pittsburgh connections, and the company Hyperloop Transportation Technologies, or HyperloopTT, on the technology. The first phase of this plan would connect Pittsburgh to Cleveland to Chicago, with phase two stretching from Minneapolis to Cincinnati to Toronto, and phase three branching out to the East Coast.

According to a feasibility study conducted by engineering firms AECOM and WSP USA that was finished in the fall, travelers could spend around $30 on a ticket for a Midwest Connect Hyperloop ride from Pittsburgh to Columbus in about 20 minutes. The trip from Chicago to Columbus would take about 30 minutes, meaning that it would theoretically take less than an hour to go from Pittsburgh to Chicago, a trip that takes nearly 7 hours by car. These hyperloop travel time estimates are based on an average speed of about 500 mph. According to the Mid-Ohio Regional Planning Commission, the completion date for their Columbus to Chicago connection is projected for sometime in the 2040s, with Pittsburgh hopefully being added closer to 2050.

Hyperloop technology involves electric, magnetic-levitation trains that use magnets to hover above the train rails while contained in an airless tube, allowing them to travel at much higher speeds than current high-speed trains. Although it’s a partly theoretical pitch, hyperloop would be a new type of rail transportation that could travel at around 600-700 mph. About a year ago, Virgin Hyperloop One reached 240 mph on its 500-meter test track in Nevada. With that test track maxed out, the company estimates, with enough track, they could reach a max speed of about 670 mph.

Walsh has been doing presentations throughout Ohio on their Hyperloop plan. Walsh says that one of the reasons for bringing hyperloop to the region is that she doesn’t see any other transportation solutions for Ohio.

“For Columbus connecting to Chicago and Pittsburgh, we currently do not have any rail service in Columbus, there’s absolutely no passenger rail and hasn’t been since 1979,” Walsh said.

Walsh said that this corridor from Chicago to Pittsburgh is a growing region that feels disserved by the lack of transportation options. She said that Amtrak doesn’t even operate in central Ohio.

“Connections to other regions is the No. 1 thing I hear when we do our metropolitan transportation plan every four years. Our community sends back to us that they want to see more inter-regional connections,” Walsh said.

Walsh said that one of the early steps for this connection would likely start in Columbus. She said it would likely be a short segment to get the project off the ground.

“Something like downtown to the airport,” she said.

In an email, SPC provided a statement from Executive Director Jim Hassinger saying that the potential advantages of hyperloop technology for the region include connecting us all in a network of technology, resources, people and jobs.

Tunneling and bridging bring additional costs to a project that, in Ohio, will mostly consist of standard, flat rails built across the region. When dealing with hyperloop speeds, that path also has to be as straight as can be, which could prevent the rail from winding through Appalachian terrain to reach its destination.

“Right now we’re still determining how much this will cost, so that will definitely be a factor,” Walsh said.

She later added that once MORPC finishes their own study, wrapping up in late December, they will be closer to an idea of how much the project could cost. “I anticipate that a baseline estimate will be included in the final report,” she said.

Ryan Kelly, Virgin Hyperloop One’s head of marketing and communications, echoed this concern, saying that tunneling would be the number one cost concern in this region.

“The more we can avoid tunneling, I think the better off we are, from just a pure cost perspective,” he said.

However, with hyperloop speeds, Kelly did float the option of the rails going uphill, something that’s not usually an option for traditional or high-speed rail.

“The ability to be able to bank and turn and actually go uphill in a way that high-speed rail or maglev trains haven’t been able to do in the past has given us serious advantage,” he said. “We can open up some of those routes and say, ‘Oh, actually, this didn’t work for high-speed rail but this can potentially work for Hyperloop.’ ”

Kelly says that the big steps in taking this regional hyperloop from idea to reality include government support, political will, figuring out exact right of ways, and building an economic case for it, with an eye towards public-private partnerships.

“The government needs to be on board with it, the public needs to be on board with it, private companies need to be able to see that there is [return on investment] from this and to potentially invest in this as well, either time or money,” he said. “I think it definitely has legs, now we’re just kind of working through that process.”

Matt Maielli is a Tribune-Review contributing writer.