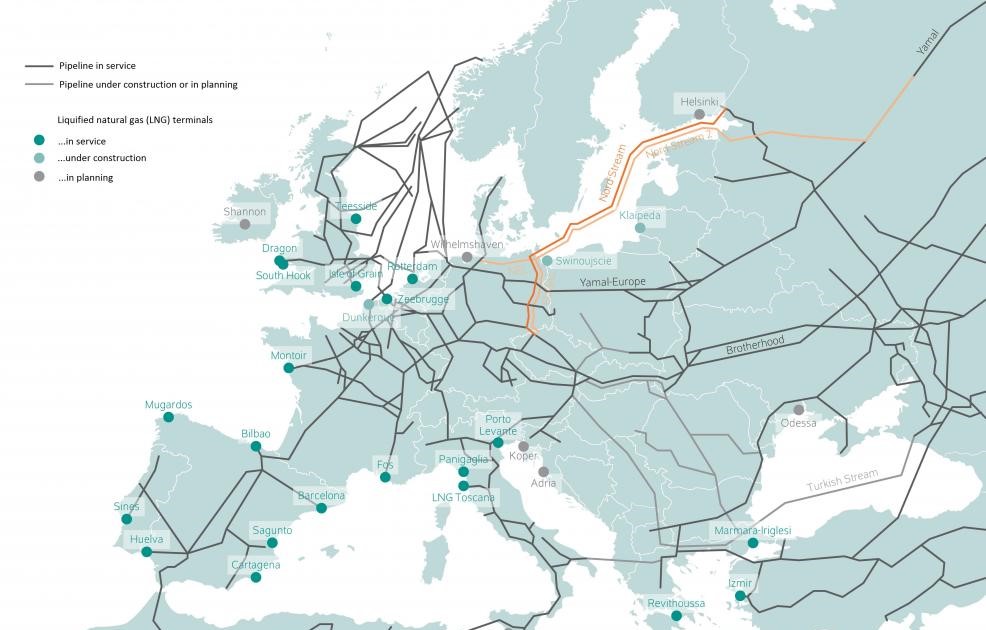

Nord Stream – a notorious Russian gas pipeline project that was staunchly opposed by the US – became the boogeyman of Central and Eastern Europe because of the obvious security threats that it poses to the region. Russia is routinely using its oil and gas supplies as a geopolitical weapon, and this project is about to provide the Kremlin with the ultimate weapon – a possibility to completely remove gas supplies from the region. The main danger here is not the risk of an energy blockade of Intermarium – how the Cenral-Eastern European region is often called – but the fact that it becomes open to all kinds of aggravated scenarios and hybrid attacks since the clients in the Western part of the continent will largely stay unaffected.

The claims lead by Germany that Nord Stream is a business project are dubious at best. The existing gas pipeline capacities that go through Ukraine and Belarus are not nearly fully used. The total annual capacity of all pipelines that go through Ukraine in the direction of Germany is 97 bcm (billions of cubic meters). Those that go through Belarus are 33 bcm. Combined is 130 bcm. During 2019 – a pre-pandemic year when the demand was high – Germany received only 57 bcm from Russia. It’s been even less afterwards.

Nord Stream is first and foremost a political project. It includes two sets of pipelines that go mostly parallel to each other. Each of them has the capacity of 55 bcm, 110 bcm total. Nord Stream 1 was fully finished at the end of 2012. After that Russia could use Nord Stream 1 and the Belarus route to supply all its gas to Europe. Ukraine wasn’t required any longer. The war in Ukraine started in 2014. Now Russia aims to finish Nord Stream 2. This will make the Belarus (and by extension Polish) route also expendable. And the political crisis in this country is already in full swing. If it escalates, Russian troops may end up at the Polish border yet again after three decades of absence, all while threatening Ukraine from the North. The rest of Central Europe will undoubtedly feel ramifications with an acute feeling of déjà vu.

The hyperloop angle

Hyperloop is a concept of high-speed transport for the 21st century which spurred quite a few promising startups. Although the idea is presented as an innovative train, it also heavily borrows from aviation, pipe transport, and self-driving cars. At its core, the idea is quite simple – by removing air resistance and friction pods can move on tracks at speeds close to the speed of airplanes. This is achieved by using a well-established technology of maglev trains and placing them into tubes with partially removed air. The result is not only a faster and greener form of transport, but it is also more efficient. It is much cheaper to operate due to reliance on electricity and lack of moving parts, it is less expensive to build than modern high-speed trains, it requires less space around tracks, it eliminates commute to and from airport by bringing people into a city center, smaller pods make routes more personalized without unnecessary stops, and many other benefits.

But, perhaps, the biggest benefit of all is that it changes societies by transforming spread-out cities into subway stops within one conglomerate, increasing cooperation and opportunities. It literally shrinks the distance between the cities down to commute between boroughs of one megapolis. You will be able to live in one city, go every day to work in another city, have your night out in a third city, and visit your mom in a fourth city. All within one day, if needed.

The key potential hyperloop projects are in the United States, India, the Middle East, and China. There are also local R&D hyperloop initiatives in Spain, Canada, Switzerland, and the Netherlands. But a strong argument can be made that the best place for hyperloop to succeed and to make the most significant and lasting impact is in Central and Eastern Europe, in Intermarium.

Below are several arguments that make Central-Eastern Europe a good target for the hyperloop technology:

- AVAILABLE SPACE. One of the main legal and budget challenges for new tracks in the Western markets is the acquisition of land. Most of the Intermarian region is significantly freer with the use of this resource than the Western markets where you can hardly draw a line on a map without stumbling into an ownership or a use restriction conundrum.

- INFRASTRUCTURE UP FOR UPDATE. Lots of existing infrastructure was laid back in the Soviet times, and it is up for an update anyway. Why not spend this money on forward-looking tech as opposed to yesterday’s?

- TRACK GAUGE. Many people forget about it, but the region is physically split into two incompatible railroad systems. Broad gauge is used in the East and standard gauge in the West. Today when trains pass from Ukraine to Poland or Romania, they need to lose 2 hours minimum at the border just to wait until they change all the wheels. At the same time, the shortest distance from Bucharest to Warsaw actually goes through Ukraine, and naturally, it is never used due to the double case of this inefficiency. For this reason, the win from a united hyperloop system will be even greater than elsewhere.

- DOMINANT CAPITAL CITIES. All countries of the region – maybe with exception of Poland – are completely dominated by their capitals. The effect from connecting those capitals into a megacity conglomerate will have a fundamental effect on the entire region. It will affect a bigger proportion of the population than connecting key cities in Western Europe, North America, China, or India.

- LITTLE COMPETITION FROM AIR. Even today most of the local airlines in the region are focused on flights to outside of the region. You cannot get from Bucharest to Budapest, or from Bratislava to Warsaw without a stopover in the Western part of the continent. A united system will connect each city with all others at once without the need for lengthy detours. On top of that, local aviation is unlikely to lobby against hyperloop because it will not be a significant threat to it, as opposed to the situation in North America or Western Europe.

The geopolitical angle

Finally, the most important aspect of a hyperloop system in Central and Eastern Europe will be its geopolitical effect. Let us admit it, for realization of big innovative projects like hyperloop the business and environmental rationale alone is not enough. Like the space program in the 1950s, or a fleet building spree in the 1940s, or first highways in the 1930s, or even railroads in the 1900s – all of them had a geopolitical angle to get their first most important push.

And this is where the region of Intermarium has a clear advantage over all other regions like the US, or India, or Western Europe that quite honestly do not have much to show for this category beyond prestige. Even China, which may weave the hyperloop effort into its geopolitical Belt and Road Initiative, does not indicate any plans to invest above its local application within Chinese provinces.

Intermarium, however, can translate quantitative benefits of hyperloop – achieved speeds, saved times, reduced costs, people and goods moved – into qualitative ones – security, cohesion, and political power of the region. Hyperloop will become the backbone that integrates diverse countries which cannot be united by existing political structures into an organism with a shared goal, and thus shared interests – without jeopardizing one’s sovereignty.

Hyperloop may lead to the evolution of hypercities – transborder nods in the hyperloop network that operate outside of national constraints akin to charter cities. Such cities may require key opposing players like the US and China as security sponsors and brokers. This will establish the Intermarian hyperloop nods as global players, something that individual countries of the region can hardly achieve. As such, the region will receive a new level of international involvement and guarantees that will help to protect it from the future Russian-German initiatives that are often detrimental to the region.

Nord Stream is a project that deteriorates the security of the region by making it less important. Hyperloop does exactly the opposite – it increases the importance of the region by making it front and center of the trans-European network. And it will create global hubs that transcend limitations of nations without encroaching on their sovereignty.

Perhaps, it is no surprise that such countries as Slovakia, Ukraine, and Poland already started exploring this technology. Slovakia and Ukraine by signing a memorandum with Hyperloop TT, and Poland through its domestic startup Nevomo, previously known as Hyper Poland. However, in all of those cases the initiative makes sense only if neighbors get eventually involved. Hyperloop is the best at medium distances that surpass the boundaries of Intermarian countries.

Potential resistance – first of all from Russia and partially from Germany – is also malleable. The network will eventually connect Moscow to Europe as well. And Moscow doesn’t have any other route to bypass it if it wants to be connected. The leading hyperloop startups – such as Virgin Hyperloop and Hyperloop TT – both have sizable Russian stakes in them, although not big enough to dictate policy. And if Intermarian politicians find a suitable formula to involve the US and China, German and Russian “realpolitiking” will have natural limits.

Hyperloop is a powerful geopolitical tool whose full potential is yet to be manifested. Politicians of Intermarium do not even need to put aside their differences in order to benefit from it. On the contrary, hyperloop allows preserving the diversity of the region and even thriving from it.

Technological progress opens a completely new dimension to foreign policy. Creating social structures that are based around technological networks as opposed to political agreements may become the next step in geopolitical evolution. In a way, it is comparable to the evolution in the animal kingdom where vertebrates came to replace exoskeleton arthropods. The carrying structure that defines a new organism is moved from risky external borders to an internal backbone, making it more flexible, better designed for growth, and less vulnerable to damage at its extremes. And Intermarium needs to move fast if it wants to make sure that the heart of this new structure is on its side.